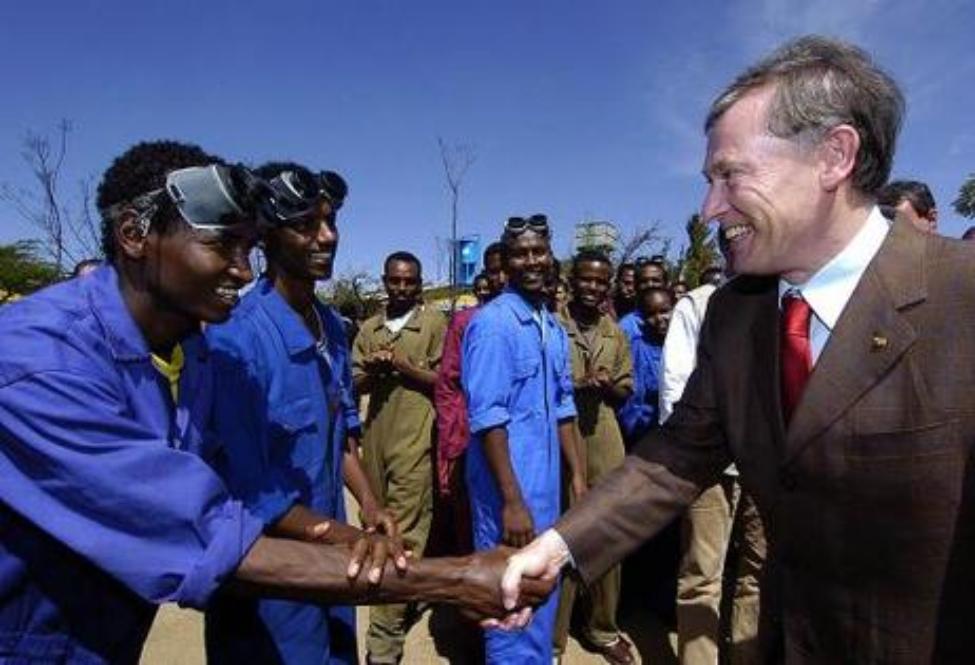

Die Zeit: Mr Federal President, in your inauguration address in the German Bundestag you said: "In my view, the humanity of our world can be measured against the fate of Africa." Your first major trip abroad was to Africa. Why does Africa mean so much to you?

Horst Köhler: In Africa I have seen with my own eyes poverty, hunger, death and chaos on a scale that exists nowhere else. But I have also met people who simply will not accept defeat. It is extraordinary with what persistence the women particularly struggle to build some kind of life for their children. However daunting the difficulties, they face them with a fortitude and dignity such as I have never encountered before. If we are serious about ethical standards, about making our world more humane, we cannot forget this continent or abandon it to its fate.

Die Zeit: The lowest life expectancy, the highest child mortality, 30 million people who are HIV-positive, war and famine - these are the usual tales of woe from Africa.

Horst Köhler: But behind those tales of woe there are also signs of hope. School enrolment levels are now rising, for example, albeit still far too slowly. People have better access to water. And in areas where AIDS is not rife, people are also living longer.

But I do not want to make the situation out to be better than it is. There are trends we cannot overlook which show that something in Africa is going dramatically wrong. As I see it, however, that is absolutely no reason for now abandoning Africa. It should prompt us instead to think again about how our development policies could be improved and what Africans themselves could do to change matters.

There is one factor we should always bear in mind: everything takes time. Africa's states are only forty or fifty years old, founded on a terrible legacy of slavery and colonialism that destroyed much of their cultural roots. And now here these countries are in today's globalized world but lacking their vital roots. We cannot expect the impossible. Nor should we forget that in Europe, in our own societies, it took many hundreds of years for democracy and the rule of law to grow deep roots.

Die Zeit: You have now launched a Partnership with Africa initiative, which aims to bring together African leaders, entrepreneurs and writers with representatives of Germany's political and business communities. What is the idea behind this initiative?

Horst Köhler: During my years abroad and my time at the IMF especially I became closely acquainted not only with the problems of the African continent but also with the hypocrisy and double standards practised by the industrialized countries. In the North-South dialogue both sides are still far too prone to talk not with but past each other and that, I believe, is one of the reasons why progress here has been so halting and slow. The purpose of this forum is to attempt to launch a real dialogue - I emphasize the word "attempt!" The forum will, I hope, be an opportunity to ask questions - an opportunity for countries of the North to put their questions and for the Africans to put theirs, an opportunity to ponder both the questions we need to ask ourselves and the questions the Africans ask themselves. They need to find out first of all what they as Africans want and then define what kind of outside assistance can best help them achieve it.

Die Zeit: Who are your political partners in this new Africa initiative? Do they really exist, this "new generation of responsible African leaders"?

Horst Köhler: First of all we must always be aware of Africa's diversity. There are a thousand Africas, countless different tribes and languages. That must be constantly borne in mind, lest we draw the wrong conclusions from talks with particular individuals.

For the first event of this initiative we have invited presidents and former presidents of countries in Africa that have successfully embraced democracy - Joaquim Alberto Chissano from Mozambique, for example - as well as representatives of civil society, some of whom take a very critical view of their own leaders and of development policy as a whole.

We also want to bring thinkers, writers and journalists into our discussion. The point of the whole exercise is not to reaffirm what we think we know, for good or ill. What I am hoping for is to bring together a core of people keen to work with me on these issues over the next few years. I hope this will be an exercise in building trust.

Die Zeit: Do you see this as a national project or are you planning to invite representatives of other western countries to join you?

Horst Köhler: No, I decided to confine this initially to Germany. But our subsequent events will be open to people from other countries as well. To be honest, I chose to start out really modestly, in the hope that the atmosphere within this very mixed group of people will allow tensions and contradictions to come out into the open and enable us to break new ground together.

Die Zeit: It is more difficult than it used to be to sell new Africa initiatives. In our affluent societies people are now having to tighten their belts, development aid is increasingly controversial and some people even want to see it stopped altogether.

Horst Köhler: My intention with this initiative is not to rehash everything that has been said about the UN's Millennium Development Goals or what should happen at the next WTO trade round. Nor is it primarily to raise more money in Germany for development aid. Money is not the main problem. What I want to do is raise awareness that we are all part of the human family, that we inhabit one and the same world and are all dependent upon one another. And yes, there is a moral dimension, too, I want to highlight the need for a global ethic. I believe we need to discuss issues of social justice more and more in a global and not merely a national context.

But of course there are very concrete interests at stake, too. If self-sustained development in Africa does not take off, the results in terms of migration, disease and environmental problems will catch up with us, whether we like it or not. We need to realize that progress here is in our own best interest. And we need to realize that protecting the rain forests, for example, improves our own prospects of effectively managing climate change and ensuring the world remains a place fit to live in. To meet this challenge, we clearly need the support of Africa and the other developing countries as well.

Die Zeit: But surely you want this dialogue to come to some practical conclusions? Is there not every justification for asking when the promised 0.7% target of GDP for development aid will finally be achieved? Do you expect this target will actually be reached one day?

Horst Köhler: It is a firm commitment, so we have a duty to achieve it and to do so if at all possible by 2015. On that point I am adamant, although I know people argue the money is not well spent. That is certainly in some cases true. That is why on my first trip to Africa as president I spoke out pretty clearly on this issue. In Benin in a public discussion I took part in the audience was more or less stunned at first by my comments on corruption and then burst into loud applause. The women especially, the small traders, the padres and nuns who run the centres for AIDS patients are constantly pointing out what a huge problem corruption and mismanagement is, when politicians and officials line their own pockets even with money intended to combat AIDS. Nevertheless, positive and encouraging developments do exist, for one thing, and for another, kleptomania and mismanagement are to my mind no reason to wash our hands of Africa.

Die Zeit: Radical African economists such as James Shikwati from Kenya call for an end once and for all to this terrible aid, which - so they say - simply strengthens corruption, dependency and lethargy.

Horst Köhler: There is nothing wrong with helping people - we have a duty, after all, to help our fellow men and women. And if this help has a negative impact, we have to find out why and correct it. That is my approach. That means, I believe, we are entitled to ask the Africans to become more efficient, more credible and to combat home-grown corruption with greater vigour. For it would be disastrous if increased aid and trade on our part were not matched by greater resolve, greater transparency and greater honesty on the part of Africa.

The core problem of poverty in Africa is indeed home-grown, so to speak. We could go on forever about colonialism, but the fact remains that today Africa is ruled by sovereign states. It is crucial therefore that they acknowledge their responsibilities - including the responsibility and the need to shape their own future.

Die Zeit: But is it not important to take a still harder line towards the corrupt élites?

Horst Köhler: We need to speak a very clear language here. But we must also beware of patronizing Africa yet again. And regrettably there are too many cases of corruption in Africa where the industrialized countries, too, are tainted, where private-sector wheeler-dealers or even political circles are involved. In Africa itself there is growing awareness of the problem of corruption. Civil society in particular is campaigning vigorously against it. These efforts we have to support.

During my time at the IMF I recruited Abdoulaye Bio Tchane, a former finance minister from Benin, to head the Africa Department. He has worked intensively on the problem of corruption in Africa and written an impressive book about it.

It was from him that I learnt what a complicating factor tribalism in Africa is. Often the only way to hold the state together is to ensure that all the different tribal groups get something. In Africa that is still done to some extent through the development aid budget. A state that consists of 200 tribes is very difficult to hold together.

But in saying that I do not want to take anything back. When talking to the recipient countries we need to speak a clear language. I still observe a tendency to be overly diplomatic and it serves no useful purpose.

Die Zeit: Should aid be tied to more stringent conditions, should Africans be told in plain words: Without human rights, without democracy, without an independent judiciary, there's no deal?

Horst Köhler: Definitely yes, there need to be conditions. But that cannot mean imposing on the Africans western-style democracy or social structures. We are entitled to call for progress on democracy, universal human rights and good governance, but we have no right to expect Africa to copy western models. I would also like to discuss what we can learn from Africa.

Die Zeit: During your time as head of the IMF did you ever get the conditionality wrong, on the matter of debt levels, for example?

Horst Köhler: In that particular instance I think probably not. The shortcomings in the work of the IMF and the World Bank have more to do with whether their operations are sufficiently geared to the long term, to building healthy structures in state and society. Above all there is too little follow-up, too little focus on what is and what is not working and why. During my time at the IMF, by the way, I was very keen to increase the scope for African countries to invest in health and education. And some headway has been made, government spending in these areas has in fact risen. This kind of conditionality has thus had a positive effect.

But I also well remember the president of one African country who visited Washington with a hundred-strong entourage. The visit along with the various purchases it entailed probably cost around five million dollars. By comparison, the construction of a granary in his country would cost something like two million dollars. And then he came to me and told me: Our people are starving. In a case like that you simply have to say: Mr President, with a more modest delegation you would have had the money for the granary.

Die Zeit: And what did the president say to that?

Horst Köhler: He was shocked and offended. He spoke excellent English and he knew all the right things to say in Washington - but in the end we simply talked past one another.

Let me come back to my other point, so people understand what I really mean. There is only one way helping Africa will work: the way it is done must be an African way, one that is in tune with African culture and character, that has an African profile. But the red line is where the cliques feather their own nests and corruption and mismanagement go unchecked.

Die Zeit: The Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto argues that property rights and rule of law guarantees would achieve more than any intervention from outside. Should we leave Africa to its own devices?

Horst Köhler: In a situation of rising chaos and even more people dying, we cannot just stand idly by. I have discussed the whole issue with de Soto. On one point he is quite right: If there was such a thing as protected property and land rights in Africa, people would indeed have assets they could use as security for loans. That could lay the basis for sustained economic growth and the development of an efficient private sector. But here, too, there is one thing that must be taken into account. In most tribes in Africa the consensus is that land belongs to God or to their chief. Nothing is achieved if land and property rights are imposed from outside. Africa needs to find its own way of defining property rights, one that is in keeping with African culture - a possible model might be long-term leases, for example.

Die Zeit: Some of Africa's own development experts argue provocatively that one reason for its plight is the African mentality. Africans, they say, are simply mediocre and indolent.

Horst Köhler: I cannot accept that western-style personal ambition and drive is necessarily the best model for Africa. Nor can I accept the idea that Africans are born lazy. In his books the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe constantly revisits one central theme: partnership in the true sense of the word will be possible only when you whites regard us blacks and our culture as on a par with your own. That is a view we in the North should listen to and also take on board. But of course that is no reason for anyone in Africa to shun commitment and hard work. Without that Africans will always lag behind, always be dependent on others. That cannot be a good thing and nor is it worthy of Africa. This remains a risk, however, unless Africa's structures are improved.

Die Zeit: ... and unless a dictator like Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, whose policies are systematically ruining his country, is put out of mischief!

Horst Köhler: I detect in Africa a growing awareness that there is a pan-African responsibility for Zimbabwe. But it is also true that Rhodesia under Ian Smith signed up to land reform as part of the independence accords, the aim being to achieve a better balance between the white farmers and the black majority. But there was constant foot-dragging. At that time the cost of implementing the reform would have been 50 million pounds.

When I broached the subject to Mugabe in 2000, my impression was that he was prepared to enter talks on the basis of the proposals drawn up by the United Nations Development Programme UNDP. At that point the issue was perhaps not given the attention it deserved in Pretoria, London or New York.

Die Zeit: Does that mean you had fairly low expectations of Tony Blair's latest G8 initiative on Africa?

Horst Köhler: This Summit I would see in a positive light, actually. But despite all the rhetoric it is also true that world leaders still do not take the situation in Africa seriously enough. It is seen as irrelevant both to elections at home and to the power constellations in the UN Security Council. Reform of the UN and the Security Council is sorely needed, but what is really going on in all the debates on the issue has more to do with jockeying for power and prestige than with anything else. It is further proof that our leaders do not see Africa as particularly relevant.

Die Zeit: But does it not start being relevant when - as we have just seen - hundreds of refugees try to cross the border fences of the Spanish exclaves in Morocco?

Horst Köhler: Of course. But the problem is apparently still not seen as really serious. From various quarters in Spain and elsewhere in Europe I imagine we will again hear vociferous calls for more aid for Africa. That is o.k. But even more important is to recognize that we have to rethink this aid for Africa, notably in terms of what it means for us.

Die Zeit: With their so-called NEPAD programme the Africans have created new mechanisms to promote good governance. Is it not a bitter disappointment that in the case of Zimbabwe they have failed to apply them?

Horst Köhler: It certainly is bitter. But we should not see Zimbabwe or indeed Côte d'Ivoire as representative of Africa as a whole. After all, some fifteen countries have now signed up to the Peer Review Mechanism. In these matters time and patience are of the essence.

Die Zeit: You have said partnership with Africa needs staying-power. How many years will your initiative run?

Horst Köhler: It will run the whole term of my presidency. What I am planning is to organize one or two events every year, primarily meetings and discussions. I very much hope these will be the kind of discussions in which everyone takes one another seriously. For then they will also be productive.