For the cultural world there is almost no greater tragedy than for a library to be destroyed by fire. So for anyone even slightly interested in culture it came as a shock when on 2 September 2004 the Anna Amalia Bibliothek went up in flames and unique treasures were lost for ever. In his book Michael Knoche vividly describes the horrors of that night - reading it, one can even now be moved to tears, as were those who witnessed the conflagration at the time.

Why were so many people so deeply moved by it? Because libraries are very special places. That people still know this even in the audiovisual and digital age is clear from the shock and grief caused by the fire and the irreversible loss of part of our culture and tradition - a grief felt not only here in Weimar, not only in Thuringia, but all across Germany and far beyond.

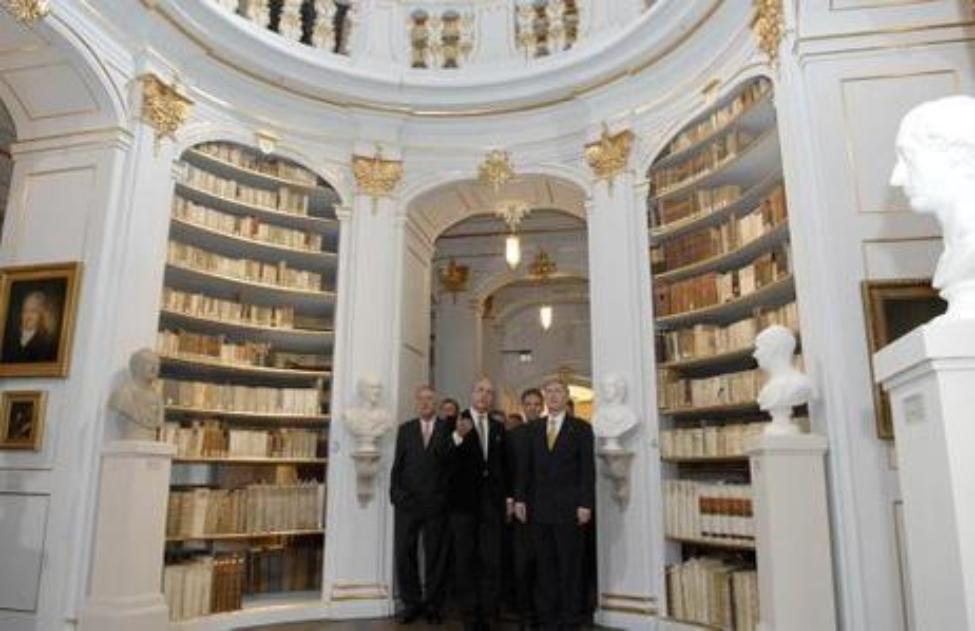

How much people value and appreciate this special place, this library, is clear from the many donations that have poured in to rebuild it. Besides the federal and state governments, foundations and companies, over twenty thousand ordinary citizens have contributed to this unique initiative. To all those, great and small, who have given so generously let me say a very special thank you. This common effort is a splendid and truly inspiring example of how strongly we in Germany feel about culture. And we can all be rightly proud of this. We are gathered here today for the reopening of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Despite all that has been lost for ever, this is a day of rejoicing for a nation that treasures culture.

But let me add right away: what we are celebrating today is only the first stage. The Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek will continue to need our support if the restoration of its contents is to be as great a success as the restoration of the building itself. The next stage - restoration of its books - is due to be completed by 2015. If you have seen with your own eyes one of these sadly charred volumes all stuck together, you realize what a huge amount of work it involves to restore each one to a usable condition. I hope very much this work will continue to be generously supported. We have fantastic treasures to preserve and restore. This we can all work on together over the years ahead.

Libraries are very special places, after all. Some years ago there was a bestseller in which a library played the leading role, so to speak: "The Name of the Rose" by Umberto Eco. I expect most of you know it. The tale is set in the fourteenth century in an Italian monastery, in whose library and scriptorium some mysterious energy is concentrated.

This library exudes an air of power. For good and for evil. It is banned to everyone except the librarian himself. He is described as someone who "devotes his life to this war with the forces of oblivion, the enemy of truth".

The abbot explains to his guest, William of Baskerville, why the library is so important for the monastery: "A monastery without books is like a city without prosperity, a fortress without troops, a kitchen without utensils, a table without food, a garden without herbs, a meadow without flowers, a tree without leaves ... "

What the abbot says about the small community of a medieval monastery is still valid today, I think, and also for society as a whole: a country without libraries is like a city without prosperity, a garden without herbs ...

Why do people value libraries - and hence the books they contain - so highly? As I see it, it has to do with the fact that the book has become a metaphor for knowledge and understanding per se. By the same token reading, too, is a metaphor for understanding. Whatever we are striving to understand appears to us as a kind of book, a script that we must learn to read or decipher.

The philosopher Hans Blumenberg gave a book he wrote about this phenomenon the intrigu¬ing title "The Readability of the World". Even in relation to the natural sciences with their formulae and abstractions, we use the metaphor of script and book to describe how they arrive at their insights: researchers have "read in the book of nature", we say, or - with regard to the latest chapter in this never-ending book - have cracked the genetic code, the script that lays down the form and structure of every living organism.

Also of people we know well we say: we can read him like a book.

To perceive the whole cosmos as a script or book, a written text that can be read and its meaning understood is an idea that goes back to ancient Jewish and Christian traditions.

In the Book of Genesis God created the world through his Word alone: "And God said, Let there be ..." - and it was! Hence language is written, as it were, into the whole of creation. Christianity invokes this ancient Jewish belief in the famous opening of the Gospel According to St John: "In the beginning was the one who is called the Word. And with this Word God created all things. Nothing was made without the Word."

A world whose building principle is the word is, in principle, a world of reason. "Logos", the Greek word used by St John, means both "word" and "reason".

According to Goethe - and here in Weimar a brief mention is certainly not out of place - any¬one who denies this principle of reason, the primacy of the word, of language, will end up in the clutches of the Devil.

Faust, the hero of Goethe's famous tragedy, decides to translate the prologue of the St John's Gospel. His first attempt starts along familiar lines: "In the beginning was the Word". But then he breaks off, saying: "I cannot concede that words have such high worth." After several more attempts he settles for the version: "In the beginning was the Act." And that is precisely the moment Mephistopheles - the Devil in person - appears and the "Tragedy Part I" takes its course ...

The word's rightful place is the book. The book is the place where - through ciphers and script - the world becomes accessible to reason.

And what care, what consummate artistry has gone into the making of those manuscripts and codices that have come down to us!

It was not just because the early books were hand-made that such care was lavished on them. Even after the invention of printing few other articles of daily use were made with such skill and loving attention to detail. A few weeks ago I was privileged to visit the Bible Museum in Münster and admire - to cite just one example - Walton's Polyglot Bible. On every double page of this magnificent work the same Bible text is printed in Latin, Syriac, Greek, Coptic and Persian. Every version set in lead type in a different script - and, as modern research has shown, without a single mistake. The book itself is an absolute work of art.

Libraries are very special places. That is certainly true of course for the Anna Amalia Bibliothek, not only because of its wonderful architecture and beautiful rococo hall but also because of its superb collections of books and manuscripts, music scores and maps, globes and portrait busts that are part of Germany's cultural heritage. Much of it is unique.

Part of its uniqueness is its history, the history of the Anna Amalia Bibliothek. The most glorious chapter of its history was written when Johann Wolfgang Goethe was State Minister in Weimar and for 35 years its top librarian. Outstanding works of German literature were produced with the aid of its collections. Wieland, Goethe, Herder and Schiller were regular borrowers. All the Weimar authors owed much to the intellectual resources assembled under this roof. Most of the books they borrowed and used still exist today. And I am looking forward to holding one of them in my own hands.

For many people Weimar and this library are a kind of spiritual home. It was the threatened loss of this spiritual home that prompted such amazing generosity - and that is the good thing about the tragedy. Weimar is where Germany's cultural heart beats most strongly. So much that Germany has given to the world had its origins here in Thuringia and what was formerly Anhalt. Luther, Bach, Goethe, the Bauhaus and much more besides. Over three centuries this was a hive of intellectual activity practically unrivalled in Europe. It is the task of our generation to preserve for the future these monuments and historical collections of national standing. For as Paul Raabe, the doyen of German librarians, rightly pointed out, "As a European city of culture Weimar is a national responsibility."

When libraries are as wonderful and beautiful as the Anna Amalia Bibliothek, it is easy to be thrilled by them. But as Federal President I would like to use this special day to give at least a passing glance to the everyday reality of libraries in our country.

First of all the good news: there still are libraries in Germany. And even better news: there are fantastic libraries in Germany. Some months ago I had an in-depth discussion with fourteen librarians from all over Germany and from very different establishments. From the huge Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin to Bielefeld University library and Chemnitz city library. Rarely have I met such a committed group of people so full of enthusiasm for what they are doing. I came away deeply impressed - and also very optimistic.

I heard about so many ideas and projects for making libraries places bustling with life and attractive particularly to children and young people. Take the summer reading club, for example, originally an initiative of Brilon town library in the Sauerland. If children can prove they have read three books during the summer holidays, they receive a certificate and that counts towards their grades in their school reports. Such cooperation between schools and libraries is an excellent thing - and there are now 150 libraries involved in this initiative. That is really fantastic - and I hope there will soon be many more.

Another excellent thing is the enormous amount of time many people - women especially - devote to library work. Our public library service, for example, is supplemented by the Borromäusverein's 2,500 Catholic libraries and 23,000 library volunteers.

At present it can rightly be said that we have a nation-wide network of libraries in Germany. That is as it should be, libraries foster the skills needed to independently access information in all types of media. Librarians provide orientation in navigating both the real and the virtual media worlds. As helpful and competent pilots they also offer guidance in exploring the infinite expanses of the Internet.

Germany's libraries - and I mean all of them, from the highly specialized research library to the small neighbourhood library - are an indispensable pillar of today's knowledge and information society. Public libraries are neither a luxury we could do without nor a burden reluctantly inherited from the past: they are an asset we must turn to the very best advantage.

In my discussions with the librarians I also learnt of the problems they face - and I am glad to take this opportunity today to draw public attention to them.

In some rural areas public libraries are already pretty thin on the ground - in some areas they even appear to be a doomed species.

Only about 15% of schools have their own library and even these rarely meet even minimum library standards.

The university libraries often lack the funds for necessary new acquisitions. They may be forced to stop subscribing to journals or continuing a research series, which all tends to reduce the value of their stock.

Despite the important contribution libraries make to education and independent learning, in Germany - unlike high-scoring PISA countries - libraries are not treated as a key part of our education infrastructure. Neither at state nor federal level is any real thought being given to the role libraries could play in achieving education policy goals. In my opinion that means libraries have to be put onto the political agenda.

The opportunity to participate in cultural life, in other words, to have access to art and culture, to history and scientific thought - that is the right of every young person. Not just our schools but also our public libraries are educational venues of crucial importance. So we must equip them accordingly - so that they can help young people discover how much fun and how rewarding it is to explore new worlds of knowledge and culture, to experience the thrill of learning.

Libraries are the collective memory of mankind. We must preserve this memory and this knowledge intact, so it will also be of service to future generations. We must ensure also the long-term preservation of our cultural heritage in printed and digital form. The libraries are already very active in this field, for they know the long-term preservation of our scientific and cultural heritage is one of their core tasks.

Many old libraries in Germany are not equipped with the latest fire safety devices - and their books, it has been said, are often in good order but in poor shape. Action is urgently needed, I hear, to take forward, for example, the mass deacidification of woodpulp paper produced between 1830 and 1990. Priceless music scores and manuscripts are at risk of damage from iron gall ink. Old covers are in urgent need of repair, for now they are included in online catalogues, older works are being loaned more frequently. An equally big challenge on which action is now urgently needed is the long-term storage of electronic media, for unless this problem is tackled, the host of digitization projects in libraries will have no long-term benefit.

In recent years also libraries, archives and museums have been required to make savings. The budgets of many institutions are currently below what is needed and their staff are overstretched. Many are no longer able to adequately perform their tasks of preserving and providing access to information. Here I hope to see a change for the better.

The cultural heritage preserved in our libraries, archives and museums is a spiritual home for the whole nation. We need this home, also and especially when we look ahead, when our sights are set on the future.

I have just given you a somewhat bleak picture of the situation our public libraries have to struggle with daily. That is what I had promised the librarians at the end of our discussion - and I always try to keep my promises. And on an occasion such as today there is perhaps a good chance that this will fall on ready ears.

For like the abbot in "The Name of the Rose", I believe a country without libraries would be like a garden without herbs, a meadow without flowers ...

Here in Weimar things are once again starting to bloom and blossom.

Thank you very much.